Over a Haveli: Gulabo Sitabo and Contemporary Contestations

MUHAMMED NOUSHAD reads Shoojit Sircar’s Gulabo Sitabo in the context of India’s contemporary conflicts on identity, heritage and even citizenship.

The octogenarian actor Farrukh Jaffer of Gulabo Sitabo, somehow reminds one of the nanis and dadis of Shaheen Bagh, as her remarkable character Fathima Beegum has got certain resemblances to those elderly women sat at the Delhi-Noida highway, to protest against the Citizenship Amendment Act. However, in Shoojit Sircar’s movie, Fathima Beegum sits nowhere other than her own time worn haveli; nor does she shout any slogan, except a few infuriated admonitions leveled at her exceptionally unbearable husband Mirza, adorably performed by Amitabh Bachchan.

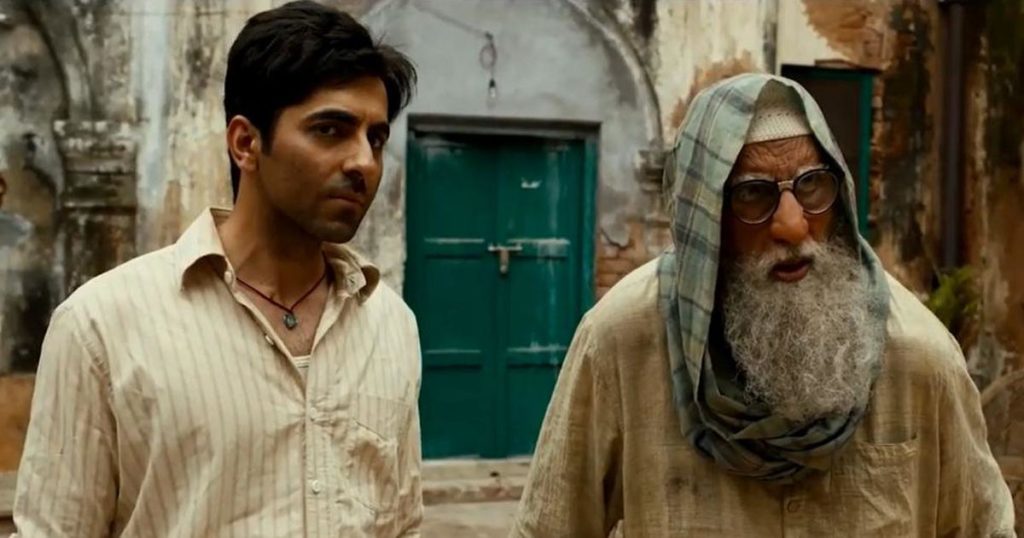

Contrasts apart, the similarities are compelling. As much as the Shaheen Bagh ladies wanted (and still want) their right to citizenship reserved intact, against the shrewd designs of a xenophobic government, Fathima Beegum needs her haveli guarded from the wicked avarice of her husband. Further, puzzling up things into a mess, the game is large and the stakeholders are many, most of them clandestinely targeting to take over the haveli. On the one hand, a corrupt archeology official Gyanesh Shukla (Vijay Raaz in his usual ease) has schemes on behalf of a political leader, and on the other hand, an aggressive developer Munmun ji is preparing to pull down the mansion for his real estate project, with the help of a lawyer. Caught between the greed of these cunning men, a lonely elderly woman, apparently unaware of the legal or political entanglements, fights a silent battle and wins, quite hilariously. On the sidelines, the perplexed tenants also wage a pitched battle, led by miserably impoverished Baankay Rastogi (wittily played by Ayushmann Khurranna) to secure their rights, and are eventually outwitted by the state, the quintessence of being aam admi. Notwithstanding the heavy allegories, Gulabo Sitabo is a fabulous movie to watch, about greed and resilience, love and loss, people, and property.

Every character in the movie has a claim for and connect with the haveli, as relationships and contestations are built around it. And the haveli, imminently collapsible and already collapsing, is multiverse in metaphor. For instance, Mirza’s haveli is not Beegum’s haveli. He wants to own it, for the sake of owning it and is eagerly waiting for the death of his wife, who is curiously 17 years older than him. Beegum’s attachment to the haveli is harmless and nostalgic, it is her life’s love, her past, and identity (even the haveli is named after her, Fathima Mahal). Greed is often akin to love, both defy logic, self-devouringly. And in the parallel drama that evolves, what the archeologist look for all over the haveli is not what the real estate sees in its totality. State uses power, capitalism uses the same thing, in a different way, on the rare occasion when they come into combat. In many ways, Juhi Chaturvedi’s layered script is also about the unending tensions of modernization in India.

The film is perfectly set in a conscious, vibrant old Lucknow, with its rich Nawabi architectural heritage, from the grand arched Darwazas of the walled city to the Imambadas filling the screen frequently. Interestingly, all-important heritage sites of the old city are even listed by the archeologist, almost like a reminder. The azans of the soundtrack are countless: a welcome relief amidst the ascending clanging and swooshing of swords, by random Muslim villains from history, unendingly invading the neo-saffron screens of Bollywood in recent years. Hence, a normal Muslim neighbourhood by itself is reassuring. Avik Mukhopadhyay’s charming camera captures the neglected, overlooked, discriminated grandeur of the old city and the long, elegant verandahs of the dilapidated mansion. Despite the evident negligence and motivated abandonment, the aesthetics of the heritage still shines through.

More than once, in an ostensibly amnesiac mood, Fathima Beegum refers to Nehru and even threatens to get Mirza arrested by Nehru, yet again giving a wind of timelessness crossing over the haveli. This film, in its totality, has a geriatric vintage-ness all over it, from props to sets to character make-overs. And, although the contestants are many, right from the concerned state departments to self-styled patrons (in this case Mirza) to capitalist bidders to tenants, nobody actually cares for the haveli, except the clueless owner.

The female characters effortlessly outdo their male counterparts with wit and charm in several memorable moments. The chaste tahzeebi Urdu of Lucknow that the characters speak is noticeably sweet. The typical gulabo-sitabo, the popular glove puppets who relentlessly fight each other, are not just the tenant and the landlord, to say the least, but India’s much-debated and non-reconcilable clash of modernity and tradition, too.

[This review was originally published in Maktoob Media: https://maktoobmedia.com/2020/09/26/over-a-haveli-gulabo-sitabo-and-contemporary-contestations ]