‘Chamkila’ Reminds What Bigotry Can Do to Cultural Expressions

Amar Singh Chamkila, a self-made performer hailing from an underprivileged Dalit Sikh family from rural Punjab was a real-life hero, a victim and a martyr. MUHAMMED NOUSHAD reviews the biopic directed by Imtiaz Ali.

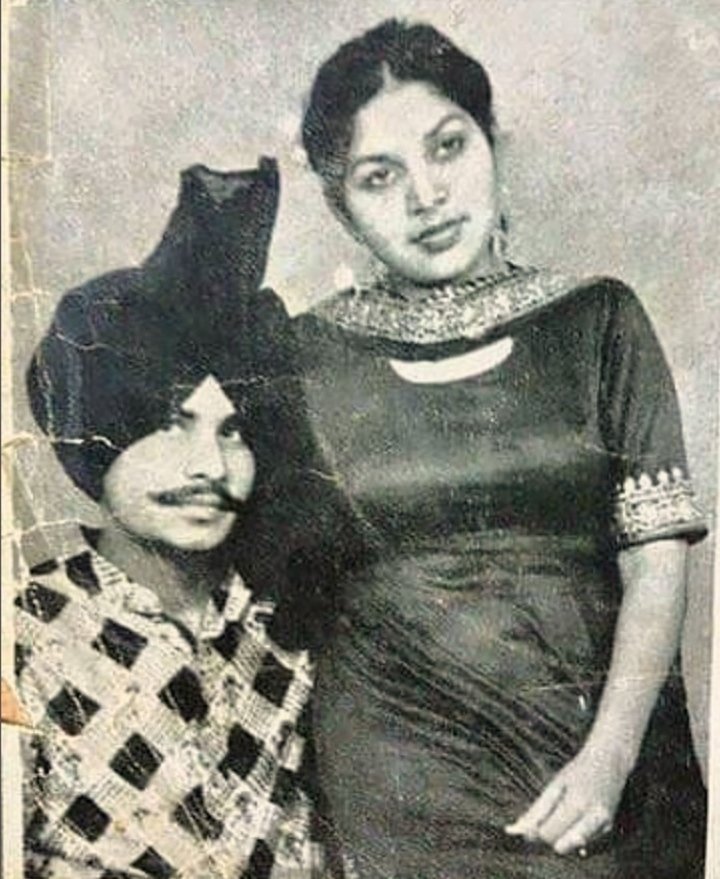

Amar Singh Chamkila was a man of controversies and contradictions. The highest-selling artist in the history of Punjab’s music industry, Chamkila was gunned down in 1988 by “unknown” assailants, when he was 27, at the peak of success. Alongside, his second wife and singing partner Amarjot and two musicians were also shot dead, as they were proceeding to perform on a stage in Mehsampur. Imtiaz Ali’s biopic Amar Singh Chamkila dramatically opens with this assassination and unveils the story of the singer and his epic journey.

Imtiaz Ali is known for his deeply introspective narratives of complex human emotions and bonding. Co-written with his brother Sajid Ali, this is probably the most courageous story Imtiaz has so far narrated, and he does it with mastery and confidence. Chamkila’s murder mystery has never been resolved in the trouble-torn state of Punjab, not even a single arrest made, and the movie also leaves the puzzle intact. Rather than answering questions, the movie seems to be interested in posing pertinent questions.

Obviously, Chamkila is not an easy character to sketch as a protagonist. As Imtiaz himself recently indicated in an interview, he had noticeable imperfections and problematic areas. So, typical glorification was the least choice. For instance, his second marriage to Amarjot itself sheds some light on his secretive and not-so-honest approach. In another scene, we see Chamkila avoiding eye contact with a female journalist while being interviewed by her, citing the reason that she wore western clothes. The journalist questions this hypocrisy effectively.

But, despite all this, Chamkila, a self-made performer hailing from a very underprivileged Dalit Sikh family in rural Punjab, was a real-life hero, a victim, and a martyr. A martyr of an elitist, casteist, militarised politico-religious culture. With the permanently attached tumbi he sonorously played with his songs, Chamkila also carried certain dynamics and symbolisms of the popular culture in India. Fame and notoriety sat together with him so easily. He could make crowds of men and women cheer up with ‘dirty and vulgar’ songs about lust and sensuality, and then enthral pious devotees with sacred religious songs: both becoming runaway hits in the market. He was frightened when he received threats from militants, but later we see a nonchalantly daring man disobeying the diktats forced upon him. This committed take on what religious fanaticism can do to cultural expressions must serve as a powerful reminder in contemporary times.

Chamkila’s life story is all about the humble beginnings of a Dalit boy as a millman, learning music, writing songs for a famous singer, then starting to perform as a substitute and then surpassing every single artist in the scene, at times, arousing professional jealousy among others. A powerful tragedy about stardom, artistic freedom and cultural dogmatism, his success story is of mythic proportions. When he ran his first (and unfortunately, final as well) show in Toronto, where Amitabh Bachchan had performed before, the organisers gleefully revealed that they had to arrange more than a thousand extra chairs to accommodate the audience. When Bachchan himself performed, it was a hundred plus chairs. However, this overwhelming accomplishment doesn’t excite Chamkila, rather we see him gloom-faced, despite being a lifelong Amitabh fan. Imtiaz Ali captures the intricacies and dilemmas of the singer in his vibrant journey of gain and loss.

When his “lewd” lyrics with erotic themes are challenged by religious authorities, Chamkila asks one question: am I the only person who sings these kind of songs? He adds, there are many Punjabi singers who sings songs that are more obscene than his. There is a feminist angle as well: that his lyrics objectified female bodies. Using the women’s voice from rural Punjab, the movie elaborates, in a flamboyantly shot song sequence, these frivolous romantic songs with explicit sensuous content have always been there in the region, and they were not Chamkila’s invention. Just like men teased women, women also teased the men in return. What Chamkila did was that he explored the genre further and gave his voice, literally, to a louder and wider audience. Perhaps, an antidote to the chaste mainstream Hindustani music sensibilities, which often did the same thing in subtle and implicit ways, and Chamkila sang his songs with assertive energies, in high-pitch from the throats of a rural, underprivileged Chamar boy, evidently entertaining every cross-section of the society. That was why his ‘dirty’ songs crossed sales records even in the black market.

The militants and the clergies were not the only institutions of power that stood in his way. The music industry has its abusive and exploitative pressures. On the one hand, the cheerful Punjabi crowds would appreciate his songs and ask for more, when, on the other hand, the songs were banned by militants and clergies for being dirty and vulgar. And Chamkila, like a true entertainer, never says no to his audience. This dilemma lands him in trouble, of course. Then, comes the role of the state, where high-ranking police officers intimidate Chamkila for having contacts with the militants. They even threaten him to finish off, if he stays in touch with them. We see an ordinary man caught in the middle of all this perilous conundrum.

The movie offers insightful reflections about the political, religious and cultural lives of Punjab, from the 1970s to the 80s, with nuance, and without much stereotyping. At times, using a documentary style, with several real-life photographs and historical footage – including that of the 1984 anti-Sikh massacres – unobtrusively interwoven with the fictional ones, the movie flows with ease and vigour. However, the caste angle of the hero is grossly underplayed; in many contexts, the Dalits and Blacks have used loud profanity to challenge the hegemonic cultural milieus in which they were subjugated and disrespected. The binaries of sacredness and profanity in art and music could open new doors of debate here.

The performances by Diljit Dosanjh and Parineeta Chopra in the lead roles are captivating, as their live performances – which is a significant and recurring part of the movie – keep us spirited and energised. AR Rahman, as usual, does his ear-pleasing job adorably, borrowing tunes and elements from Punjabi folk music and recreating Chamkila’s hit songs. The farewell song not only serves as a closure to the movie, but it also tells us that the storytellers are not interested in resolving the puzzle, even in fictitious ways, but making us think of new questions about artistic expression, freedom, religious and political interventions in our lives and sensibilities.

[Madhyamam English carried this originally: https://madhyamamonline.com/entertainment/movie-review/chamkila-reminds-what-bigotry-can-do-to-cultural-expressions-1281790

Thank you Noushad. Skilfully written and highly readable.