An Obituary for Kerala’s Fast Dying Hills

Book Review

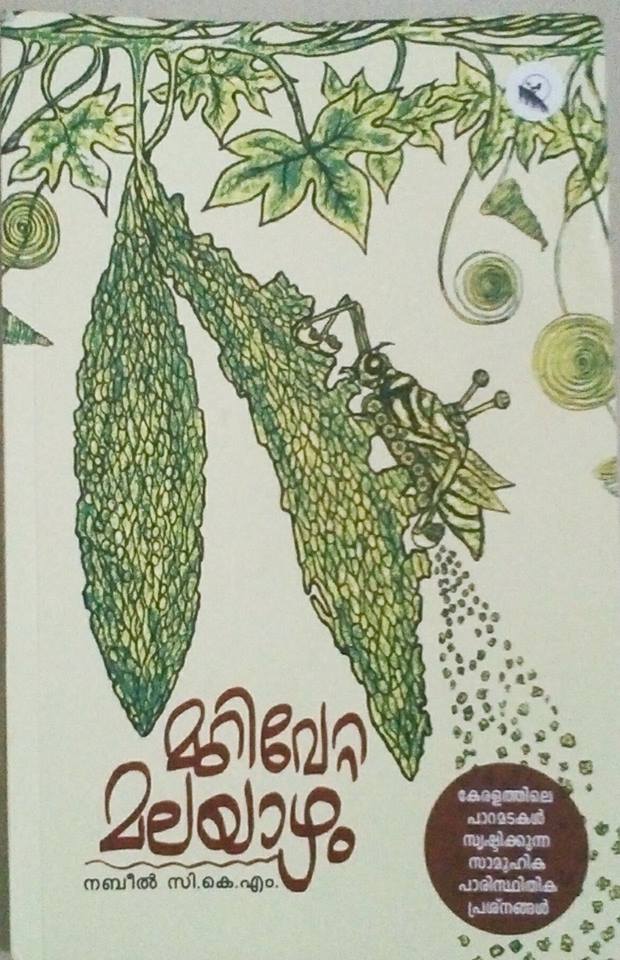

Nabeel CKM’s Malayalam book on the stone quarries and the mining mafia in the Western Ghats of Kerala exposes the socio-political pathologies of our times.

MUHAMMED NOUSHAD

When Keraleeyam, an exemplary magazine that has set its standards in reporting environmental issues and human rights, comes up with a full length book, it does offer something original and unique. Murivetta Malayazham: Keralathile Paramadakal Srishtikkunna Samoohika Paristhithika Prashnangal (The Wounded Mountains: Social and Environmental Threats Posed by the Quarries in Kerala) is an outstanding exploration of a young writer on the issue of quarrying and mining in Kerala.

Nabeel CKM, a freelance journalist, photographer and activist, undertook this project when he was awarded with Keraleeyam’s annual Biju S Balan fellowship. Usually, the fellows produce a commendable monograph that could run into one or two coverstories of the reputed magazine. But Nabeel’s journey was too deep to be confined to a few pages of Keraleeyam monthly; his commitment deep and the paths painstaking, he dug data over data and brought about insight after insight, traveling to almost all agitation sites in the breadth and depth of the Western Ghats. The perspectives he shared with his mentors at the Keraleeyam desk were so overwhelming that they decided to get his writing published in the form of a book.

“While going through the people’s struggles against quarry operators across Kerala, Nabeel got involved and forgot that he is a media person writing about the mining issue. He started engaging in the struggles and could no longer keep the professional distance that one is often asked to keep between oneself and one’s subjects..” Photo by Shafeeq Thamarassery.

What eventually resulted was a brutally honest obituary of the consistently decaying and fast dying ecology of Kerala. In many ways, this 150 page book is a contemporary history of the ethical dilemmas and pathologies of the socio-political life of a state that has often been slapped with generous honorifics in developmental discourses. Nabeel critically examines, with convincing arguments and evidences, the malignant paradigms of development that has been constantly overusing all natural resources available. The book exposes the illicit nexus between the stone quarrying lobby, political parties and the big time construction contractors.

To quote Keraleeyam editor S Sarath, “While going through the people’s struggles against quarry operators across Kerala, Nabeel got involved and forgot that he is a media person writing about the mining issue. He started engaging in the struggles and could no longer keep the professional distance that one is often asked to keep between oneself and one’s subjects. Keraleeyam had also been contemplating something beyond routine reporting of quarrying issues. In no time, we agreed on this remarkable book.” However, in no ways, this was not an easy book to write, as Nabeel painfully explains in his preface.

Stone quarrying is rampant across the crestline of the Western Ghats in Kerala. Most of these sites are located in ecologically sensitive areas. The Kerala Forest Research Institute, Peechi, had found out in a study that there are 5,924 quarries in the state, covering an area of 7,156.6 hectares.

The government agencies, including the department of mining and geology, doesn’t appear to have taken any serious note of the danger that indiscriminate mining – legal and illegal – would eventually bring forth to the people and the nature in the state. The landslide susceptibility and seismicity are directly linked to the disproportionate mining and hydrological systems are largely affected.

The book has a detailed chapter on the environmental and geological challenges that the stone quarries and crusher units pose to the state. Going by the recommendations of Prof. Madhav Gadgil, who chaired the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP), is the way ahead. But, what the state saw was a high level miscommunication campaign and heated controversies over the Gadgil Committee report and eventually, as Nabeel discusses in the book, a diluted and dishonest version called Kasthurirangan report.

The complex power relations the quarry industry has established with the ruling political parties are enough to put democracy in shame. The book scrutinizes the complicity of all major parties, from CPI-M to BJP, in different struggles against stone quarries and crusher units, and it is eye-opening to see that all of them have taken unambiguously anti-people stands to favour the quarry mafia. On the other hand, the people, very ordinary men and women with no thorough geological understanding of the issue or legal protection or financial resources to bargain with the power lobbies, are fighting tooth and nail to win their lives and livelihoods. The way we neglect and betray these genuine battles are a sign of how politically insensitive we are.

The book has a long chapter to deal with the inadequacies and the incapability of the existing laws regarding the quarrying issue. For example, the Kerala Minor Mineral Concession Rules was postulated in 1967, long before the massive machineries and earth movers came into existence. Of course, before the neoliberal economic policies, too. The book further argues that the amendment brought forth in 2008 by the LDF government – termed as Consolidated Royalty Payment – was extremely faulty, unwise and anti-people. The rules that conveniently allows short-term and temporary licenses for mining are dangerous and extremely harmful to the nature and the people. No rule ever seeks actual compensation for the people around. And there are very systematic and widely practiced strategies to bypass the regulations, through its own potholes. The way drinking water, air, and other essential resources are polluted and put to no one’s use is terrible. The loss of water goes beyond human life; it affects animals, birds, reptiles and much more. The dark dust from the crusher units create health hazards in the surroundings. Agricultural sector is directly affected in umpteen places.

The book proposes a meaningful coordination of the scattered struggles as all of them invariably raise same questions and offer similar solutions. The reader comes across common patterns of corrupt local administrations supporting the quarries, goondas settling issues physically, police taking sides with the miners, bureaucratic hurdles, financial difficulties of the people as the quarry mafia try to purchase people and leaders very often, et al. The final chapter has a remarkable list of 14 recommendations by the author to resolve the issue on a long term basis. But, who is listening?

The book is more enriched with very useful and enlightening appendices – historical leaflets produced by anti-quarry and crusher agitation committees, relevant commission reports, geologically significant maps etc. This would have been a gloomy and pessimistic read but for the fighting spirits of the author and the Keraleeyam collective. Instead of drawing cynical conclusions, the book offers strategies for a legendary struggle that everyone who believes in the earth and life, will have to wage, today or tomorrow, against all odds.

Disclaimer: The reviewer is a friend of Nabeel CKM.